3. 1. Shearing and binding

From the Middle Ages until the early 19th century the main tool for shearing grain was the sickle, also known as the hook (Fenton 1985, 114). In 16th century Scotland the saw-toothed sickle was commonly used in the Lowlands (Fenton 1985, 115-116), and there is evidence for a small semi-circular smooth-bladed sickle being used in the Northern Isles between 1633 and 1900 (Fenton 1985, 116), while a broader smooth-bladed version was the standard tool in southern Scotland from the end of the 18th century (Fenton 1985, 116) (fig. 3.1.1.).

Experiments carried out in the late 18th and early 19th century regarding the use of scythes for cutting cereal crops were initially unsuccessful, especially in the south of Scotland, due to the absence of smooth, stone-free ground prior to the development of horse-drawn rollers as well as to many farmers’ belief that scythes were inclined to shake the grains off the stalks (Fenton 1976, 120). However, since they speeded up the work, scythes steadily gained popularity for grain harvesting in northeast Scotland, where, unlike in the south, there was a shortage of manpower; they remained the main grain cutting tool until their replacement by horse-drawn reapers in the second half of the 19th century (Fenton 1985, 122).

The development of horse-operated reaping machines has been regarded by many as the revolution in harvesting technology (Fenton 1985, 125). While there are references to mechanised reaping-implements as far back as the works of Pliny and Palladius, modern experiments began in the late 18th century (Langlands et al. 2008, 256).

Numerous early versions failed; those with scythes attached to furiously rotating wheels tore up and trampled the crop, and others were too complex and fragile to be practical (Langlands et al. 2008, 256-257). The turning point was the development of Cyrus McCormick’s reaper, patented in 1834 in the U.S. and exhibited at the Great International Exhibition in London in 1851 (Fenton 1985, 128) (fig. 3.1.2.). One of the first effective designs, it cut the grain with a knife going back and forth and was drawn by a team of horses walking in front of the machine and along the side of the grain (Fenton 1985, 128).

By the 1860s horse-drawn reapers were becoming popular in most parts of Britain, and the development of the ‘reaper binder’, which had an integrated mechanism for binding the crop into sheaves, in the 1870s further increased its usefulness and appeal (Langlands et al. 2008, 257)(fig. 3.1.3.). In the 1930s tractor-drawn reaper binders were in use alongside horse-drawn ones (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010).

Arguably the most significant development in 20th century arable farming, however, was the combine harvester, which threshes the grain as it cuts (Fenton 1976, 89). The 1934 Royal Show exhibited American combine harvesters, but in those early days only very few were used in Britain, usually on large estates (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010) (fig. 3.1.4.). However, as part of the World War 2 drive to increase food production self-propelled combines were leased from America (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). Since the introduction of combine harvesters better suited to British conditions after the war the number in use has increased steadily (Blandford 1976, 133) (fig. 3.1.5.).3. 2. Threshing

In the 16th and 17th century grain was threshed by various manual methods, generally throughout the winter months (Langlands et al. 2008, 258). There are references to flail-threshing in Scotland from 1375 onwards (Fenton 1985, 138) (fig. 3.2.1.); other methods commonly used in various parts of Britain included rubbing the ears between bare feet- to preserve the straw for thatching- (Fenton 1985, 36-37), people treading the sheaves, lashing the ears against hard or toothed surfaces (Fenton 1985, 134-137) and plucking the grains by hand (Fenton 1976, 52).

The introduction of threshing machines caused much resentment in the major grain-growing areas of Britain, since it deprived many rural labourers of what was often their only source of employment in winter (Langlands et al. 2008, 258). Their anger found expression in protests and uprisings such as the infamous Swing Riots of the early 1830s, when threshing machines were destroyed and wheat ricks set on fire (Langlands et al. 2008, 261) (fig. 3.2.2.; fig. 3.2.3.).

However, the spread of threshing machines continued apace. The first ‘threshing mills’ were fixed installations in barns (Langlands et al. 2008, 258). Early models were water-powered, based on mechanised flails and rather dangerous (Fenton 1976, 83). The first fully successful design was patented by the Scotsman Andrew Meikle in 1788; powered by a horse, the sheaves were fed through a pair of rollers into a revolving drum, where the grain was knocked out by velocity (Fenton 1976; Langlands et al. 2008).

Before the 1830s threshing machines were powered by water, horse or wind (Fenton 1976, 87). On farms where water was used as the motive power, mill-dams and mill-lades became part of the layout, along with water-wheels alongside barns walls (Fenton 1976, 87). Where horses were used as the power source, circular horse-walks, either covered with overhead gearing or open with underground gearing, were built against the barns (Stephens 1860; Fenton 1976) (fig. 3.2.4.; fig. 3.2.5.).

In his ‘Book of the farm’ Henry Stephens describes how the threshing power source influenced the most advantageous siting of a farmstead (Stephens 1860, 79). Threshing machines quickly replaced flails on many larger farms (Fenton 1985, 133), though Stephens (1860, 495) mentions flail-threshing still being common practice.

From the 1830s onwards steam power replaced horse-power for threshing machines, in part because the machine’s juddering motion was detrimental to horses (Langlands et al. 2008, 258), and tall chimney-stacks for the coal-fired boilers appeared on farms (Fenton 1976, 87). A further important development came in the form of moveable threshing machines, which contractors hired out to farmers (Fenton 1976; Langlands et al. 2008) (fig. 3.2.6.). On small Scottish crofts flails were gradually replaced by small hand- or pedal-operated threshers from around the 1830s, but flail-threshing was practised well into the 20th century (Fenton 1976, 89).

When tractors came into widespread use from around the time of World War 1, the tractor pulley was used to drive the threshing machine (Fenton 1976, 89), and finally the advent of combine harvesters, first tractor-drawn and then self-propelled, which thresh the grain as they cut, eliminated the need for barn threshing-mills (Fenton 1976, 89). However, many smaller farms stuck to older proven technologies which did not necessitate great expenditure. In Scotland horse-driven threshing mills, for instance, did not completely disappear until the second half of the 20th century (Fenton 1976, 89).

3. 3. Winnowing

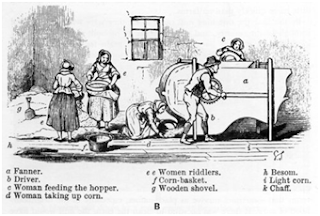

Until the early part of the 18th century winnowing was carried out by hand, either in the open air or in a through-draught in the barn, using a skin stretched over a wooden rim (Fenton 1976, 93). Winnowing machines, also known as corn fanners, were introduced from the 1730s onwards, becoming components of threshing mills (Fenton 1976, 91) and eventually of combine harvesters (Blandford 1976, 131) (fig. 3.3.1.).

No comments:

Post a Comment