2. 1. Field systems

From the Middle Ages to around the middle of the 18th century the open-field system with a three-year rotation of crops predominated English agriculture. Typically wheat was followed by barley and then by fallowing (Langlands et al. 2008, 23). By the 16th century the staple crops were peas/ beans, barley and wheat, though their proportion could vary significantly between individual farms (Hoskins 1951, 10-11). The introduction of clover, lucerne and sainfoin (fig.2.1.1.) into arable rotations around the mid-17th century contributed to an increase in grain yields (Thirsk 1997, 25).

Fig. 2.1.1. Sainfoin (‘Wild flowers of Magog Down -

the pea family (leguminosae)’ 2008a)

However, the open-field system with a three-year rotation never reached Scotland (Fenton 1976, 11), whose characteristic pattern of subsistence agriculture remained fundamentally unchanged from around the third or fourth until the 18th century, and even longer in the Highlands and Islands (Fenton 1976, 3). Open-field farming with mixed husbandry was still the typical system in the English Midlands by the early 17th century (Hoskins 1951, 10), while a four-part rotation of bere (fig.2.1.2.), oats, wheat and peas was being introduced in the main wheat-growing areas of Scotland (Fenton 1976, 11-12).

Fig. 2.1.2. Bere

(‘Agronomy Institute research on bere’ nd.[m])

The 18th century, however, witnessed a dramatic transformation of the agricultural landscape of Britain. Enclosure- which had begun in the late 17th century in areas such as southern Scotland (Fenton 1976, 14) - led to a gradual disappearance of the open field system (Langlands et al. 2008, 23). Between 1700 and 1845 some 4000 acts of enclosure were enacted by Parliament (Mazoyer and Roudart 2006, 340).

From around the mid-18th century onwards the Norfolk four-course rotation, using crops such as wheat, turnips, barley and clover, began to gain popularity, and its development and adaptation to local condition continued into the 19th century (Langlands et al. 2008, 23). The Scottish Highlands and Islands saw a gradual conversion of the run-rig system into small consolidated holdings from around the mid-18th century onwards, although it survived in isolated pockets well into the second half of the 20th century (Fenton 1976, 24-25).

In Britain as a whole, however, the Agricultural Revolution of the 20th century had consequences every bit as far-reaching as those of the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). While in the 1930s most grain was produced on small farms by large labour forces of “men and horses” – as the Mud, sweat and tractors TV programme put it, apparently blithely ignoring the huge contributions of women and children in all aspects of farming (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010) -, developments in all aspects of technology, combined with a policy of government subsidies from World War 2 onwards (more on this below), led among other consequences to the draining of wetlands and the elimination of hedgerows in order to facilitate the consolidation into fewer, bigger and more specialised farms which characterised the second half of the 20th century in particular (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010).

2. 2. Population pressure and politics

Following a prolonged decline after the Black Death, population numbers began to rise again from around the year 1500. The resulting increase in the demand for grain and the looming spectre of shortages and civil disturbances led to renewed government emphasis on cereal production. Farmers were encouraged to plough up grassland and conversely punished for putting arable land down to pasture. Together with more intensive rotations and the application of more fertilisers these measures resulted in a significant increase in cereal harvests (Thirsk 1997, 23). In the 1640s productivity and specialisation increased even further in order to feed the Parliamentary army at war in England, Scotland and Ireland (Thirsk 1997, 25).

The second half of the 18th century saw a repeat of the same pattern, with another increase in population once again putting the emphasis on grain production and more grass- and heath-lands being brought into cultivation, as well as small farms being amalgamated into larger units (Thirsk 1997, 147). In the Highlands and Islands of Scotland agrarian capitalism in the form of increased rents, enclosure and the ‘Clearances’ erased many old villages and hamlets and depopulated entire areas (Fenton 1976; Symonds 1999).

Both cultivation and consumption of grain in the 19th century were significantly influenced by the passing of the Corn Law in 1815 and its subsequent repeal in 1846. This law was designed to protect British agriculture by banning the import of wheat when the average price of home-grown wheat dropped below a certain value. It therefore found favour with many farmers, but met with violent opposition from urban populations of all classes who objected to bread prices being kept artificially high, although Sheppard and Newton (1957, 60) argue that it had in fact less of an effect on the price of bread than expected. After the repeal of the Corn Law trade in Britain was essentially free, and cereal imports rose from around 1870, which in turn led to a steady and significant reduction in domestic cultivation (Borchert 1948; Fenton 2007), and a long period of agricultural depression which lasted, it has been argued, until the beginning of World War 2, interrupted only by a temporary upturn between 1916 and the early 1920s resulting from World War 1 emergency policies with short-lived results (Blair 1941; Borchert 1948; Holderness 1985).

The 1929 crisis led to a collapse of all commodities, including cereals (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). During World War 2, however, the acreage under cultivation rose once more thanks to the application of new scientific methods and technologies and the encouragement of ploughing-up of grassland through subsidies (fig.2.2.1.); not surprisingly during this period the emphasis was on increasing the quantity rather than the quality of grain (Blair 1941; Borchert 1948; Holderness 1985; Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010).

Fig. 2.2.1. Land girl learning to plough

(Guardian 2009)

Facing a severe food shortage after the end of World War 2, the British government decided to continue its agricultural subsidy policy, passing the Agriculture Act of 1947 which guaranteed arable farmers minimum payments for their produce to protect them against the fluctuations of the open market (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). However, taxpayers from other sectors of the economy soon became disgruntled with the amount of subsidies paid to farmers, and when a Labour government came into power in 1964, political pressure to reduce them mounted, and tensions and conflict between government and farmers ensued (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010).

In 1973 the UK joined the EEC with its system of tariff barriers designed to keep out cheap wheat from other parts of the world, thus securing a huge guaranteed market for its produce, and demand for British bread wheat increased (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). Furthermore the Chorleywood Bread Process, which had been developed in the 1960s (more on this below), allowed for the use of a substantial proportion of home-grown wheat in the white loaf. The result of both of these developments was a huge increase in output, which led to the infamous ‘grain mountains’ of the early 1980s (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). Thus the introduction of set-aside in 1992, a system by which farmers were paid to take land out of production as a means of regulating supply and demand (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). Some farmers took advantage of government subsidies offered for conversion to organic production from the 1990s onwards, many doing so with the objective of making relatively small holdings profitable (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). The reduction of EU tariffs on imported wheat in the same period meant that producers found themselves once more at the mercy of the global market (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). Notwithstanding this, by the end of the 20th century the UK was almost self-sufficient in bread wheat (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). Agriculture remains a high-risk business in the 21st century, with some associations of wheat growers attempting to mitigate some of the uncertainties by striking supply deals with major supermarkets (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010)

2. 3. Soils and climate

Arable agriculture is dependent to a significant degree on soil and climatic conditions. Rye, for instance, needs light sandy soils, whereas barley and legumes do well on clay (Hoskins 1951, 14). Accordingly in the 16th century the East and the South were the main areas of Scotland for growing pulses (Fenton 2007, 201), and there is documentary evidence from the 17th to the 20th century for the cultivation of rye on a number of Hebridean islands with suitable soils such as those of the machairs (Fenton 2007, 257). From the Agricultural Revolution onwards new developments have extended the cultivation ranges of many food crops. The Norfolk four-course rotation, for example, made light soils suitable for wheat, resulting in a decline in rye-growing (Fussell 1943; Sheppard and Newton 1957), and many of the new varieties of hard wheat developed in the second half of the 20th century are suitable for less ideal growing conditions (Holderness 1985, 48 ).

2. 4. Choice of Crops

Until the 19th century it was common for farmers in various parts of Britain to cultivate different cereal and legume crops together in the same field in order to turn them into bread (Fussell 1943, 213) In Scotland peas were commonly combined with beans, oats or barley, as well as growing rye with oats or bere with barley; the result was referred to as ‘masloch’, ‘mastillion’ or ‘mashlum’ (Fenton 2007, 201; 257). From the 18th century onwards, as mentioned, more and more land was used for wheat, with the result that rye had almost disappeared by 1750 (Sheppard and Newton 1957, 71). In the early 19th century a rising demand for higher-gluten wheat coupled with an improving water transport system led to the extension of commercial wheat-growing in southern and eastern England into areas previously used for pasture or the cultivation of other crops (Petersen 1995, 163).

The introduction of scientific plant breeding can arguably be regarded as one of the major advances in 20th century agriculture (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). In the 1970s the Cambridge-based Plant Breeding Institute developed a dwarf variety of wheat with larger yields and a decreased likelihood of being blown over by the wind (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010). The institute having been disbanded in 1987, however, plant breeding today is largely carried out by commercial companies; one of the major objectives is the development of crop strains adapted to an increasing variety of climatic conditions (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010).

The steep decline in the use of horses in agriculture between around 1940 and 1970 was reflected in a comparable decline in the acreage under oats, with the exception of the Scottish Highlands, where oats have long held a greater significance as human food than in many other parts of Britain (Holderness 1985, 46-47). By the late 20th century wheat and barley had become the chief crops on British tillage farms, with both rye and maize playing an insignificant role (Holderness 1985, 46-47).

2. 5. Drainage and Ploughing

Much of the land used for arable farming in Britain is wet and in need of drainage in order to make it suitable for ploughing and eventually for growing cereal crops. For many centuries drains were dug by hand, though simple draining ploughs are mentioned in 17th century sources (Blandford 1976, 64). Major advances in drainage technology did not take place until the 19th century, with the development of several types of mole plough designed to cut underground drainage ditches (Blandford 1976, 64-65), the invention of cylindrical drain-pipe manufacturing machines in the 1840s (Langlands et al. 2008, 24) and the introduction of systematic underground tile drainage, which helped to improve both the quantity and quality of yields as well as enabling the use of new machinery (Fenton 1976, 23). Between 1846 and 1870 ca. two million acres of land were drained at public expense (Langlands et al. 2008, 24). The availability of drainage grants in the 1960s and 1970s resulted in another peak in land drainage in the second half of the 20th century (Brassley 2000, 68).

Fig. 2.5.1. Egyptian plough, New Kingdom

(‘Wooden plough from Egypt New Kingdom

(1550-1070 BC)’ nd.[l])

The earliest known ploughs were simple scratching tools which separated the soil to both sides (Blandford 1976, 44). Both the ancient Egyptians and ancient Greeks used wooden ploughs (fig. 2.5.1.) with iron shares, and there are records of wheeled ploughs from the Roman Empire (Blandford 1976, 16; 44).

Fig. 2.5.2.

Fig. 2.5.2. Rotherham Swing Plough

(‘The Rotherham Plough’ nd.[k])

While ploughs used in Britain remained fundamentally unchanged in design from before the Norman Conquest until the 18th century, there was significant regional variation as a response to differing soil and climatic conditions (Blandford 1976, 50-51). 16th and 17th century ploughs, such as the Kent Plough used on the chalk and marsh soils of southeast England, were generally of heavy construction, but lighter ploughs began being developed along the East Coast in the 18th century (Blandford 1976, 52-53). During this period the main structural components and points of wear of ploughs were increasingly made from iron (Blandford 1976, 50), first wrought and following Robert Ransome’s patent in 1785 also cast (Fussel 1948, 90). The increasing use of horses rather than oxen for ploughing during the 18th and 19th centuries stimulated many advances in plough construction, with the Rotherham Swing Plough (patented 1730) representing the first commercially successful iron plough as well as being one of the first to be produced on a factory scale (fig. 2.5.2.); its design remained standard until the advent of steam power (Blandford 1976; Langlands et al. 2008).

Fig. 2.5.3. Modern tractor ploughing

(‘The farm today’ nd.[d])

The manufacture of ploughs became highly industrialised during the course of the 19th century, with mass-produced standardised components and scientifically designed ploughs (Blandford 1976; Langlands et al. 2008). When steam tractors came into use in the latter part of the 19th century, followed not too long afterwards by those with internal combustion engines, plough attachments were developed which coupled to the tractor hitch (Blandford 1976, 70-71). The first officially–sponsored tractor trials in England, organised by the Royal Agricultural Society in 1910, featured both steam and oil-powered models (Blandford 1976, 33). It was the huge demand for food production coupled with a lack of manual labourers during World War 1, however, which gave major momentum to the development and use of tractors in British agriculture (Blandford 1976, 34). Modern high-powered tractors of the late 20th and early 21st century are able to cut a large number of furrows at one pass (Blandford 1976, 71) (fig.2.5.3.).

Fig. 2.6.1. Broadcast sowing

(‘Holy propagation: scatter, layer, cut’ 2009b)

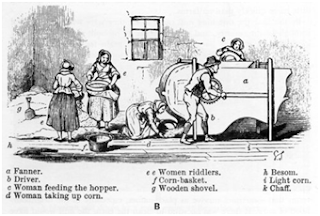

2. 6. Sowing

Before the 18th century broadcasting was the common way of sowing grain in Britain. Sowers followed the plough, carrying seed in an apron or a specially designed container called a seedlip and scattering handfuls of it as evenly as possible across the field, a method which demanded a steady hand and a good sense of rhythm (Dorrington 1998a; Langlands et al. 2008) (fig.2.6.1.). Although this technique left a sizable proportion of the seed exposed to birds and other pests, it continued in use well into the 19th century (Fussell 1952; Langlands et al. 2008). Dibbling began to be used as an alternative to broadcasting in the 17th century but did not become widespread until the following century (Fussell 1952; Blandford 1976; Dorrington 1998a), around the same time as it was itself being supplanted by the introduction of mechanical seed drills (Blandford 1976, 77).

While there is evidence for some form of seed drill as least as far back as 2800 BC in China, this device was only re-invented in Britain in the early part of the 18th century, when numerous models were designed, most of them not very practical (Anderson 1936; Fussell 1952). After Jethro Tull introduced the first successful design in the 1730s (fig.2.6.2.), the use of seed drills slowly spread through the main cereal-growing areas, not coming into widespread use until the mid-19th century (Anderson 1936; Langlands et al. 2008). While travelling seed drills could be hired by farms which did not have their own (Anderson 1936, 189), and the seed fiddle was introduced from the U.S. after ca. 1850 (Fenton 1976; Dorrington 1998a), a lot of corn was still sown by hand by the middle of the 19th century, especially on smaller farms, due largely to the cost of machinery (Stephens 1860, 31-32).

Fig. 2.6.2.

Fig. 2.6.2. Reconstruction of Jethro Tull’s seed drill

(Anderson 1936, 170)

One of the advantages of the mechanical seed drill lay in its sowing of the grain in even rows, allowing for the use of horse-drawn hoes between the rows and in turn greatly increasing yields (Langlands et al. 2008, 46). Today’s modern tractor-drawn drills cover a wide area of ground at the same time while functioning on the same principle as their horse-drawn predecessors (Blandford 1976, 79).

2. 7. Fertilising

Until the mid-19th century the only available fertilisers were organic waste materials. As well as dung produced on the farm or collected from town stables, early farming manuals refer to seaweed, oyster shells, fish, bones, horns, blood, rags, hair ashes, soot and malt dust among others, many of them by-products of urban industries (Fussell 1948, 87). The mixing of different types of soil, a process known as marling or claying, was another means of improving yields by enhancing soil structure (Fussell 1948, 87). Artificial fertilisers began making an impact in the 1840s, with nitrate of soda being imported from Chile (Fussell 1948, 87) as well as the beginning of the systematic exploitation of phosphate materials such as bones, certain types of sand and chalk (Mazoyer and Roudart 2006, 367). Guano was imported into Britain from 1840 onwards. Experiments with chemical fertilising substances at Rothamstead experimental station in Hertfordshire led to the commercial production of superphosphate manure from 1842, which, along with potash salts becoming cheaply available from 1861, allowed many farmers to free themselves from the commitments of long-term crop rotations and specialise in cash crops, with cereal growers no longer being forced to keep livestock solely for manure (Fussell 1948; Langlands et al. 2008).

World War 2 saw a doubling of the usage of chemical fertilisers in an effort to raise agricultural yields (Holderness 1985, 7). An increasing variety of chemical herbicides and insecticides became available from the late 1940s onwards, though it took another 20 years or so before their toxic effects on humans, animals and the wider environment became a matter of general awareness (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010).

Fig. 2.7.1.

Fig. 2.7.1. Miraculous new chemicals:

DDT advertisement, LIFE magazine, 1945

(‘Rachel Carson’ 2007)

The infamous insecticide DDT (fig. 2.7.1.) was banned in Britain in 1984, and general legislation regulating the use of pesticides was introduced in 1986 (Mud, sweat and tractors: the story of agriculture 2010).